The world economy has been mired in a deep crisis since 2007. The bourgeois have tried everything to climb out of the crisis, from quantitative easing, to zero interest rates, to the socialisation of banking losses, but all to no avail. Why is it that a modern-day version of Keynesianism cannot work?

John Maynard Keynes once said: “”If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise … to dig the notes up again .., there need be no more unemployment and … the real income of the community, and its capital wealth … would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is.”The old recipes, based on the mantra of globalisation, are in tatters. This is clear for all to see and it is starting to emerge not only in the specialised publications but also in the more widely read media as well. What is not stated clearly, however, is what alternative the bourgeoisie has. This is not by chance as no such alternative exists.

After years of Panglossian optimism about the fate of capitalism, the crisis abruptly put an end to any illusion of an uninterrupted development of the market economy. Everything that was considered part of the success story of globalisation was now turned into its opposite and exposed as a driving factor of the crisis. This is true especially for the financial wilderness that prepared the collapse. In this article we focus on a particular aspect of the political and ideological crisis of the capitalist class: the futile attempt to apply Keynesianism in the concrete conditions of crisis today.

That capitalism can face a deep crisis is now something Marxists have no need to explain. The orthodox modern theories (monetarism, rational expectations, efficient market hypothesis and so on) were based on the idea that laissez-faire and deregulation were everything the world economy needed to develop. Let the big corporations rule the world unhindered by the state and the markets will adjust everything and everything will be fine. In this regard, as Keynes pointed out, Jeremy Bentham [British philosopher, 1748-1832] used the expression ‘laissez-nous faire’ [let us get on with our business], which actually sounds quite different and clearer than laissez-faire alone.

At the time, the capitalist class was tightening its grip on the productive forces and did not want the old absolutist state to stand in its way. This idea, powerful against the old monarchies, was already a useless relic at the time of Keynes. Ever since then, again and again, laissez-faire ideology has crashed together with the world economy. Any serious crisis of capitalism has forced bourgeois strategists to think again about the dogmas they used to explain reality. When capitalism has an upswing, no matter how this is achieved, brainless optimism holds sway: things are working and don’t stand in our way. When capitalism crashes, bourgeois strategists are forced to look for alternatives and this was the meaning of Keynesianism. The question today is: can a new form of Keynesianism be found that can offer the bourgeoisie some kind of alternative policy that can keep the system going?

The original Keynesianism

Keynes was one of the most typical products of the British bourgeoisie. Born in Cambridge, son of a Cambridge professor, educated at Eton, he worked in India on behalf of the British Empire and then as an official for the Treasury. As a theoretician, his most important contribution was to destroy the old laissez-faire dogmas after the First World War and during the Depression of the 1930s. He was never really interested in developing a coherent explanation of how capitalism works although he tried, especially with his General Theory in 1936. The question for him was always a practical one: to force the capitalist class to understand the reality of the great crisis they were in. In the opening pages of the General Theory, Keynes clarifies this very goal: to persuade mainstream economists to re-examine economic theory and to change direction. Already many years earlier, Keynes had drawn the conclusion that orthodox economic thinking had failed: “Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is past the ocean is flat again”[1]. If they are not able to set a new trend, they are useless as bourgeois advisors and should be marginalised, as happened in the 1920s and 1930s.

Keynes succeeded in his efforts to change course as the bourgeoisie had no other choice than follow his advice in rejecting the old pre-crisis ideas. We will not deal here with the question of how and whether Keynesianism per se was useful in overcoming the Crash of 1929. We will limit ourselves only to pointing out that the ideological reshuffling was deep and long lasting. This was because Keynes interpreted a new stage of capitalist development.

Capitalism has always been about both regulation as well as automatic mechanisms. But monopoly capitalism meant that the intervention in the economy had reached a new stage. The meaning of Keynes’ proposals was that capitalism is intrinsically unstable and that the government should act permanently to stabilise it. The idea of the need for a regulated capitalism flowed from the concentration and centralisation of capital. In the epoch of imperialism, the world economy is dominated by a handful of giant corporations that plan ahead their strategies and have a decisive role on the market as a whole. This does not mean that the laws of motion of capitalism are abolished, but simply that they apply differently. Monopoly capitalism had produced new economic policies already by the time of the First World War that forced governments to implement a full mobilisation of economic and social resources. This achieved a level of economic planning that in previous periods would have been considered incompatible with the market economy.

This irreversible change of capitalism meant that to criticise state intervention as if capitalism were the same as it was in the days of Adam Smith was nonsense. The socialisation of the productive forces had proceeded immensely; and therefore an unregulated capitalism was simply no longer possible. Old automatic mechanisms, such as the gold standard, could not work anymore. In one way or another, the state would have to take the lead. This is the core of Keynesianism.

The individual practical recipes Keynesianism suggested to governments (reducing interest rates, deficit spending and so on) helped only up to a point. The real point of Keynesianism was to overcome the contradiction between the interests of the individual capitalist and the capitalist class as a whole; to save the capitalist system from its own contradictions. Embracing state intervention, explained Keynes, was not the end of the bourgeoisie; on the contrary, it was the only viable way of saving capitalism.

Undoubtedly, this new era implied a major inter-capitalist reshuffling. In the final chapter of the General Theory, famously called “Concluding Notes on the Social Philosophy towards which the General Theory might Lead”[2], Keynes is quite radical in his views. He starts by stating: “the outstanding faults of the economic society in which we live are its failure to provide for full employment and its arbitrary and inequitable distribution of wealth and incomes”. Keynes sustained that capitalism had improved on these problems but only up to a point and that in order to survive, capitalism needed “the euthanasia of the rentier”, that is the reduction of the power of financial rent via higher taxes, lower interest rates and so on. Secondly, he maintained that investment should be socialised inasmuch as it is needed for full employment. This does not imply a state-owned economy, however:

“It is not the ownership of the instruments of production which it is important for the State to assume. If the State is able to determine the aggregate amount of resources devoted to augmenting the instruments and the basic rate of reward to those who own them, it will have accomplished all that is necessary. Moreover, the necessary measures of socialisation can be introduced gradually and without a break in the general traditions of society.”

This idea seemed quite radical, but it was because capitalism had no alternative: the socialisation of investment by the state is only a reflection of the historical trend towards socialisation of the productive forces that capitalism brings about. Therefore, these ideas are compatible with a wide variety of political forms. Both Fascism and classical Social Democracy promoted huge state intervention in the economy and sought full employment, at least in their programme. Therefore, Keynesianism could be the basic economic theory of very different political agendas within the confines of the capitalist system.

Scientific merits of Keynes

Criticising the weak elements of the classical school (Smith, Ricardo, etc.), Marx took this theoretical framework to its logical conclusion showing the inevitable class struggle that emerges under capitalism. This meant that the old theory was no longer useful for furthering bourgeois rule. Therefore, after the Paris Commune, it was replaced by another with the so called mid-19th century idea of “marginal revolution”. The most important theoretical feature of this new paradigm was that it was supposedly based on the individual. It is a micro-economic theory.

According to this theory, nothing exists if it cannot be justified on individual grounds. Social and economic dynamics should be explained and traced back to the actions of individuals (“methodological individualism”). This is a strikingly futile approach as the goals of the individual are completely reversed when put together on a social scale. For instance, for the single capitalist, cutting wages to raise profits is a good idea, but when all capitalists cut wages, the market collapses and profits go down. In the same way, if a worker accepts to do overtime to raise his income it is good for him, but if every worker does overtime, unemployment goes up and wages go down for everyone. Even more clearly, the technological dynamic of capitalism is based on this contradictory aspect. The single capitalist invests to reduce costs and gain market shares and profits, but when the innovation generalises, profits go down again. Unable to understand the difference between the individual logic and the social outcome of an action, modern bourgeois economics is useless to explain the mechanisms of capitalism; neither is it used to this end.

The merit of Keynes was to start from this contradiction and re-introduce into economic theory the analysis of society as a whole. This is vital, especially to understand crises. It shows that in the long run it is pointless cutting wages to raise profits, as Keynes explained, as if we were considering single companies. This is also true when we analyse investment. The single capitalist must normally save before investing, but for the economy as a whole savings are created out of investment. In passing, we can see how the present so called “austerity measures” stem from confusion between micro-analysis and macro-analysis. In any case, Keynes emphasised the social dimensions: unemployment, investment and consumption. From this aggregate analysis, came the theoretical explanation of the crisis. Of course, practical measures to fight the crisis long predated Keynes; he simply provided a theoretical dressing for something many governments were already doing, although many were refusing to intervene following the “Treasury View”, i.e. that fiscal policy had no effect whatsoever on overall economic activity, an idea sustained in particular by the British Exchequer.

Keynes was also responsible for the introduction into economic theory of a number of subjective concepts (animal spirits, the state of expectations, the beauty contest mechanism and so on). This was not by chance. The concentration of capital, the merging of industrial and banking capital, the divorce of the capitalists from any direct role in production, and the increasing role of the State (i.e. the basic features of finance capital), also meant the complete subjectivisation of economic theory. All these concepts were used to assess the investment cycle that is the engine of capitalist dynamics.

The decision to invest depends on the prospect of a return. Future profits by their very nature have always been uncertain. But in the 20th century the concentration of capital had grown to such a degree that a single investor could play a big role in the market – big monopolies have market power. Moreover, the differentiation among the bourgeois, between pure rentiers and managers, was also reflected in economic theory in the growing weight given to psychological aspects rather than to structural, objective ones.

At the end of the day, capitalism develops if capitalists invest. But the logic of capitalism, with competition between capitalists driving down wages to increase profits, creates a fundamental contradiction: the contradiction of overproduction, in which the working class cannot afford to buy back the very goods that capitalism produces. Production – and thus investment also – grinds to a halt as commodities go unsold. When things go wrong, the state must invest directly so that the economy can bounce back and private capitalists can regain their feet. This is what Keynesianism is all about. Specific tools are a minor issue compared to the role of saving the bourgeoisie from the contradictions of its own system.

It is also worth noting that the concentration of capital and trustification of the economy also produced a debate around social planning as giant companies require planning to survive and the capitalist’s instinct is no longer sufficient[3].

From all these theories, Keynes extracted a number of specific instruments. As we said, it would be a mistake to reduce Keynesianism to a specific set of economic measures. Nonetheless, it is traditionally linked to a number of policies. We can divide these policies into four main areas: fiscal policy, monetary policy, industrial policy and financial regulation. We will try to show why none of them can work now.

The four pillars of Keynesianism

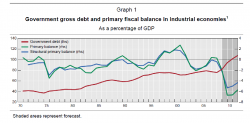

The first and most relevant set of measures linked to Keynesianism is that of fiscal policies that should be used with two main goals in mind: income distribution and public expenditure. In a nutshell, the idea is to tax the rich to have a more equal distribution of income and to raise resources to build the welfare state. As workers spend more or less all their income, taxing the rich means a boost to consumption. In fact, in the US, the top income tax rate reached 91% in the 1940s. Similar rates prevailed in Europe. At the time, fiscal policy was really a means of redistributing income to poorer people. This is no longer the case today. Since the 1980s, fiscal policies have changed in such a way that workers’ taxes subsidise the companies by a number of legal and semi-legal ways, showing that, as Marx pointed out, the fiscal struggle is part of the class struggle – and the most ancient one at that. This complete reversal in fiscal policy is deeply linked to the vital needs of capitalism. It is not only a question of low profitability, but of the way governments tried to escape this for decades: in the form of growing debt. We are in the epoch of debt and there is little room for a strong active fiscal policy as we have previously explained[4]. See this graph:

Click to enlarge Graph

It is clear that the increase of debt is something that long predates the crisis. It is linked to the historical decline of capitalism. This is what makes fiscal policy less effective, not an ideological fixation of “neoliberal” politicians. Needless to say, however, the crisis has worsened the situation dramatically, as the United States administration was forced to use hundreds of billions to save the big banks:

“Since the start of the financial crisis, industrial country public debt levels have increased dramatically. And they are set to continue rising for the foreseeable future (…). Our projections of public debt ratios lead us to conclude that the path pursued by fiscal authorities in a number of industrial countries is unsustainable. Drastic measures are necessary to check the rapid growth of current and future liabilities of governments and reduce their adverse consequences for long-term growth and monetary stability.”[5]

In the context of these structural imbalances, expansionary fiscal policy only serves to delay the problem but it also worsens it in the long run. In the decades before the crisis, leaving aside all the ideological talk of the need for the state to withdraw from the economy, its overall weight in developed countries did not change much.

The right-wing reaction against state intervention, however, had a point from a bourgeois point of view. Overall, the state does not produce anything, so it is a burden on the economy. The problem is that the more capitalism develops the less is it able to operate without state intervention. The process of concentration of capital and the financialisation of the economy are reflected in this permanent role of the state. After a quarter of a century of so-called free market globalisation, public expenditure and public debts were not reduced. The idea that Thatcher-Reagan deregulation rolled back the role of the state is a figment of bourgeois imagination, as this graph shows[6]:

Click to enlarge graph

It is clear that privatisation, deregulation, monetarism and so on were in actual fact an attempt to limit the decline of profitability at the expense of the working class. Public debt and debt as a whole were never seriously cut back. This fact is a clear indicator of the growing parasitic nature of capitalism that laissez-faire fanatics cannot reverse. A 70 year old man can dress up as a teenager and go to a disco pretending to be young, but he would not fool anyone.

The overall weight of public expenditure in the economy has not been rolled back significantly, but its role has changed considerably. Capitalists wanted the workers to pay, and all economic policy was built around this. What changed was the direction of state intervention: its resources were more and more used to boost profitability, not to provide public social services. This is true of all state policies, starting with the taxation system.

Now Keynesian economists complain this is madness, that it is unfair and that it has contributed to the disaster. Yes, it is unfair to use workers’ taxes to help big companies, yes, it is madness to cut wages directly or indirectly in a situation of productive overcapacity, but there is a method in this madness. In order to guarantee a future to capitalism, governments had to raise the rate of profit by any possible means. It is pointless, however – as the reformist left does – to complain about the ugly consequences of this vital need of the bourgeoisie if one is not ready to fight capitalism as a whole.

As we have seen, the state did not disappear from the economy even in the period of “free market” euphoria, but when the crisis hit this led to a huge increase in its intervention. For instance in the US:

“The federal budget balance as a per cent of GDP plunged from a surplus that had reached 3.0 per cent of GDP in 2000 to a deficit of 3.6 per cent of GDP in 2003, an astounding increase in borrowing of 6.6 per cent of GDP – or about $700 billion – in just three years, an enormous further subsidy to aggregate demand. During the same interval, US economic authorities welcomed a major devaluation of the dollar, the real effective exchange rate of which declined by 8 per cent (although the greenback’s fall against the US’s key Asian trading partners was more limited). All told, it was an incitement to economic growth unprecedented in US history except during wartime.”[7]

But did all these measures succeed? If success means avoiding the immediate meltdown of capitalism, the answer is yes. However, the situation is far from stable and new contradictions have accumulated at the core of the system. The state, private firms, banks and households are all submerged by debt; and using fiscal policy to postpone the problems is in fact very dangerous.

Monetary policy and inflation

This explosion of debt has also affected monetary policy. In the Keynesian schema, monetary policy has two main goals: to promote investment and to reduce wages. The first goal is obvious: the lower the interest rate the higher investment, all other things being equal. The problem is no one is interested in investing where there is overcapacity, and cheap money can produce an even bigger problem of overcapacity, as Japan learned the hard way.

After twenty years of zero rate policy, did Japan return to high growth? Not at all, as we have explained many times[8]. The new governor of the Bank of Japan, Kuroda, has now announced an unprecedented stimulus package involving the purchase of government bonds to the tune of more than $500 billion a year. This will undoubtedly provide some months of relief, but then what will happen?

For the last twenty years they tried all kinds of stimulus policy, but to no avail. Zero rate policy, quantitative easing, twenty stimulus packages, devaluation produced nothing! After all these years, government debt in Japan is now the highest in the world (more than 250% of GDP). This means that already 20-25% of government expenditure goes on paying the debt. It would be enough for rates to go up to 2-3% for the entire budget to be spent on interest on the debt. In other words, interest rates are no longer free to go up.

What yesterday was true for Japan nowadays is true more or less everywhere. Every central bank has reduced interest rates to historical minimums and has bought tons of public debt. Take the US: the Fed buys more than $500 billion of Treasury bonds a year. It already owns $1.86 trillion of Treasury securities. This is a sixth of the US public debt and growing. This means the Fed would be among the ten biggest countries in the world by GDP if it was one.

Things are going so badly that central banks are thinking the unthinkable: setting negative interest rates. For instance, the Bank of England could decide to get the banks to pay to hoard money at the Old Lady. Needless to say, “introducing a negative interest rate in the UK would be a significant further step, and one without many precedents”[9]. In Denmark this strange idea is already a fact and also the European Central Bank is thinking of charging banks that keep money idle[10]. The situation is serious because the “debt service ratio is now also at an all-time high of 13.6%. And this is with the lowest interest rates in 50 years”[11]. The situation, in many ways, is a lot worse than in the 1930s:

“A comparison with 1929 is alarming. In 1929, there was very little household debt in the US economy. Business debt in relation to profit was about half as high as it is today. And of course there was no foreign debt – the US was a net creditor to the world in 1929.”[12]

The never ending growth of debt means central banks are no longer free to set interest rates. On the contrary, they are being pushed more and more into a corner and if they do try to escape by raising interest rates, everything would crumble like a house of cards. So much for rate policy!

Central banks are now so scared of their own policies that they are trying to hold on to a real anchor: gold. Last year they bought the most gold since 1964 and now they own about 19 percent of all the metal ever mined[13].

But the fiscal and monetary policies of Keynesianism led to nasty side-effects in practice in the form of inflation. Sustained government spending on public services, infrastructure, and arms – all in the name of “demand-side management” – was an inflationary policy, i.e. money was spent that did not exist (and in the case of arms production, without creating any corresponding increase in value being circulated). Such inflation hit home in the 1970s, precipitated by the oil crisis of 1973-74. The previously unseen phenomena of stagflation emerged: economic recession alongside high inflation – something the Keynesians had previously denied could happen, since the lack of demand in a recession should put a downward pressure on prices.

For the working class, such high inflation meant a real cut in wages. Despite many bitter struggles by the trade unions for increased wages to match prices, wages could not keep up with inflation. For the capitalists, inflation created uncertainty and instability – both economic and political, in the shape of strikes, etc. Hence the turn towards the anti-inflationary – “supply-side” – policies of monetarism in the shape of Thatcherism and Reaganism. However, for such policies to work, the capitalists needed to take on the trade unions and drive down wages in favour of profits.

This trick was soon understood by the labour movement. We can already read in the Platform of the Communist International (1919):

“Workers’ struggles for wage increases, even where successful, do not result in the anticipated rise in living standards, because the rising prices on all consumer goods cancel out any gains. The living conditions of workers can only be improved when production is administered by the proletariat instead of the bourgeoisie”[14]

The 1929 depression removed inflation as an immediate threat, but as World War Two approached things changed and Trotsky, in the Transitional Programme, explained how to fight inflation seriously:

“Neither monetary inflation nor stabilisation can serve as slogans for the proletariat because these are but two ends of the same stick. Against a bounding rise in prices, which with the approach of war will assume an ever more unbridled character, one can fight only under the slogan of a sliding scale of wages. This means that collective agreements should assure an automatic rise in wages in relation to the increase in price of consumer goods.”[15]

In our present epoch of structurally high unemployment and overcapacity, many Keynesians are again relaxed about the dangers of inflation; but with large amounts of money being pumped into the system in the form of quantitative easing, the threat of inflation remains in the case that such money finds its way beyond the banks into the wider economy. We should also add that the more finance capital dominates the world economy, the less inflation is palatable to the ruling class, as finance capital derives its profit from credit and financial assets that are negatively affected by inflation.

Industrial policy

We need an industrial policy! This has been the mantra of every “left” politician since the start of the crisis. In the heyday of Keynesianism, the state directly controlled a large chunk of industry and basic utilities such as transport and energy, but also the steel industry and so on. We should first ask ourselves why this is no longer the case.

Keynes pointed out:

“The most important Agenda of the State relates not to those activities which private individuals are already fulfilling, but to those functions which fall outside the sphere of the individual, to those decisions which are made by no one if the State does not make them. The important thing for government is not to do things which individuals are doing already, and to do them a little better or a little worse; but to do those things which at present are not done at all.”[16]

When Keynes proposed to partially socialise investment, he was expressing a historical fact that Marxism had explained long before him: capitalist development means a growing socialisation of the productive forces. However, although necessary, the state directly involved in production creates a problem for capitalism. Either it manages healthy firms, subtracting profits from private capitalists, or it manages bankrupt firms, using taxes to keep them going. In both cases, the capitalists are not happy. This is the basic contradiction of Keynesianism as an industrial policy. In the golden era after the war, this was not very important for many reasons. Profits were good and the capitalists needed the state to rebuild their industries. Thirdly, the state was useful to manage sectors that were not profitable per se but yielded profits for others. At the time, the bourgeoisie could accept the obvious theoretical argument that industries that are natural monopolies should be state-owned as competition is not possible in such cases. This long term direct intervention on the part of the state created a sort of capitalist planning with state agencies, multi-year plans and so on. This was the era of “planification indicative” as the French called it. In developing countries, planning was even more important, as they had to build industry from scratch[17].

Then came the crisis of the 1970s, the collapse of Bretton Woods, the oil crisis and class struggle on the rise. Profits were falling, with the state being forced everywhere to save private industries for emergency reasons, not out of any preconceived plan, and public finances worsened by the year. In the 1980s, although there was a recovery, the rate of profit did not return to the golden age of the 1950s and early 1960s. The capitalists were desperately seeking ways of making easy money. That explains why the state was forced to sell off its best assets to private capitalists. A generalised sell off was the advice no government could refuse and basically everything was privatised. Whole economic sectors were dismantled and sold off. But public finances were in no way improved by all this; quite the opposite.

The main point we have to understand here is that the process of privatisation was not the result of some kind of ideological hatred for state-owned enterprises. The question is very simple: privatisation is a basic component of the restoration of the general rate of profit, as are the big income re-distribution in favour of the rich and the destruction of the welfare state. Capitalists are no longer in the position to allow a profitable sector to be publicly run; they need to occupy any possible economic space in order to survive; they cannot afford high wages and good social services. Basically, they literally need to make profits from everything, from water to healthcare, from schools to motorways. That is why an organic industrial policy in western countries is ruled out today.

Even when the state is forced to bail out private companies, this does not involve an actual “intervention” if we exclude the money itself handed over. In the past, after having nationalised, a bank for instance, the state would have sent in its officials to set a new strategy, the board would have been sacked and so on. Nothing of the sort happens now. Take the giant bank RBS, nationalised in 2008. After five years, what has changed in the way it operates? Nothing! Not even as far as the scandal of golden bonuses is concerned[18]. RBS is not different from Barclays or HSBC, and others big banks. Its state-owned nature does not change a thing. Indeed the Lib-Con coalition government is thinking of creating another bank to finance Small and Medium-sized Enterprises because it cannot use RBS to achieve this. The big US banks, saved by the government with the TARP (the “troubled asset relief program”), rushed to pay back the state in order to be free even from the mild conditions that came with the programme. Once again, we see how this aspect of Keynesianism also cannot be applied in present-day conditions.

Financial regulation and the financialisation of the economy

The fourth element in Keynesian thinking was financial regulation, a set of strong controls on the financial system as a consequence of the crisis of the 1930s. First of all, the banking sector was strictly divided between retail businesses and investment banking (with the Glass-Steagall Act in the US and similar laws elsewhere). Secondly, in many countries, the banking sector was mainly state-owned (Italy, France) or so strongly regulated by the state, that the result was the same: banking was a stable, predictable activity. In the US, for 30 years the industry was so predictable that observers described it as operating according to the 3-6-3 rule: bankers gathered deposits at 3 percent, lent them at 6 percent, and were on the golf course by 3pm. Strict controls on capital flows and fixed exchange rates were also part of the framework. Results were good: financial crises, an inevitable part of the landscape for centuries, disappeared:

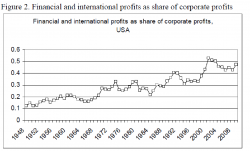

“Until the Great Depression, major crises struck about every 15 to 20 years — in 1792, 1797, 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893, 1907, and 1929-33. But then the crises stopped. In fact, the United States did not suffer another major banking crisis for just about 50 years — by far the longest such stretch in the nation’s history. Although there were many reasons for this, it is difficult to ignore the federal government’s active role in managing financial risk.”[19]

It is just too easy for a Keynesian economist to remark how stable the situation was in the era of financial regulation, lamenting the present situation. Strong state control was something finance capital could afford in an epoch of extraordinary economic growth. After the collapse of Bretton Woods, the crisis of the 1970s and so on, financial regulation was dismantled piece by piece. Exchange rates became flexible, capital controls were scrapped, and the Glass-Steagall Act was abolished (by a Democratic President by the way). Deregulation, self-regulation, light touch regulation, all kinds of pro-banker policies were adopted. The sheer weight of banks and finance on the world economy started to grow. Merger after merger created banks so big that in 1984 the term “too big to fail” was coined to describe this new situation. When that term was invented, in the US one bank alone had total assets of more than 3% of GDP. In 2007 there were nine such banks – and this in the world’s number one economic power. In the EU countries the situation has become farcical, with some banks bigger than the country that hosts them, so that it is now very obvious that the country is hostage to its big banks. Iceland or Cyprus come to mind. The weight of the banking sector has grown to unprecedented levels[20]:

As noted by Crotty:

“The value of all financial assets in the US grew from four times GDP in 1980 to ten times GDP in 2007. In 1981 household debt was 48% of GDP, while in 2007 it was 100%. Private sector debt was 123% of GDP in 1981 and 290% by late 2008. The financial sector has been in a leveraging frenzy: its debt rose from 22% of GDP in 1981 to 117% in late 2008. The share of corporate profits generated in the financial sector rose from 10% in the early 1980s to 40% in 2006, while its share of the stock market’s value grew from 6% to 23%.”[21]

Part of this madness was the colossal real estate bubble that was, overall, the biggest bubble in history.

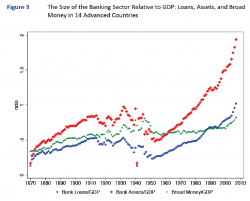

As the balance of forces among capitalists is established by profits, the best picture of finance capital domination of the world economy is given by the distribution of profits. Although banks employ a small fraction of the total labour force, nowadays they take between a third and half of total profits[22]:

Click to enlarge graph

The growing decay of capitalism means a growing weight of finance capital. Understanding this trend is the key to understanding capitalism today, including the impossibility of forcing the banks back to financial regulation. Bourgeois strategists do not deal with this issue, as we noted when looking at the IMF document quoted above.

The question is clear: debt (or credit) is the only tool capitalism has found to delay a crisis that is the result of its own internal contradictions: the previous fall in the profit rate in the mature sectors, overproduction and slow economic growth. Although the profitability of companies bounced back in the 1980s for a number of reasons that we have explained many times, this was achieved only with an enormous and expanding amount of credit, i.e. of debt. Debt was needed to get things moving. This was a further help to the big banks in taking the helm of the world economy.

First of all, they got rid of any serious public control (“deregulation”). Secondly, the public supervisors (central banks, etc.) were told – by politicians and by the banks themselves – to mind their own business, reaching the farce of accepting the banks’ own method of calculating the risks of their activities (the so called “Basel 2” agreement). Financial innovation, i.e. the creation of all sorts of strange derivatives to make money, flourished.

One would think that the serious strategists would have anticipated the collapse of this giant house of financial cards. On the contrary, an orgy of optimism was celebrated. Greenspan and co were the heroes of the day. Just before everything was about to collapse Greenspan explained in his autobiography: “I would tell audiences that we were facing not a bubble but a froth – lots of small, local bubbles that never grew to a scale that could threaten the health of the overall economy”[23]. How clever on his part!

It was easy to see already a decade ago how the more the financial system was deregulated the more it was prone to producing bubble-collapse cycles, with crises that were more and more frequent and bigger until it all exploded in 2008. Some timid voices of dissent started to be heard just before the crisis:

“There are serious reservations about the sustainability of the financialisation process. The last two decades have been marked by rapidly rising household debt-income ratios and corporate debt-equity ratios. These developments explain both the system’s growth and increasing fragility, but they also indicate unsustainability because debt constraints must eventually bite.”[24]

He went unnoticed. Then, all of a sudden, every central banker, every economist, and every policy-maker woke up to the sudden reality: the big banks were putting world capitalism in jeopardy. They rushed to re-regulate banking and a whole series of new rules are under discussion or have already been adopted.

And yet, nothing changed significantly, because nothing could really change. Banks are not ruined because their top managers are greedy. Modern day capitalism cannot function with bankers that are not greedy and mad for profits. No amount of new rules will change this. On the contrary, if they do force banks to be more prudent, cutting their profits, they will push them towards even riskier behaviours at a later stage.

The big banks consider the new regulations a nuisance, but they know that in reality national governments are in their pockets, and they have only to wait some time before everything can get back to business as usual, including golden bonuses and so on. Even now, after years of crisis, after the banks have been saved with public money, they do whatever they want. Keynesian economists are very angry about this, but this cannot change the historical situation of capitalism.

The historical trajectory of Keynesianism

When the First World War broke out, the state was forced to mobilise all the economic and social resources that were available for the war effort. A strong presence of the state in industry was mandatory in these circumstances and public debt exploded as a consequence. After the war, the European economy was in a bad shape. The pre-war “automatic” levers that had been put in place to ensure economic growth were no longer there. After years of vain attempts to return to the gold standard and liberal capitalism, the 1929 Crash ended that world for ever. State intervention (and the reformist leaders of the labour movement) saved capitalism from the abyss. No matter what the political stance of the government was, it was forced to rush in to save industry. The successes of the planned economy in the USSR also played a role to this end.

After WWII, strong public intervention in the economy was in place everywhere. From being an emergency rescue package, now Keynesianism became the orthodox policy in all capitalist countries. The western bourgeoisie accepted strong public intervention for political reasons, but also because profitability was good. The economies was growing, profits were high so everything was fine. The state invested in infrastructure, in public utilities and in economic sectors that were scarcely profitable in the short term. Wages were growing and unemployment was low so consumption grew apace. Many banks were state-owned, speculative finance was irrelevant and Bretton Woods was a good imitation of the gold standard. Everything seemed under control. In the underdeveloped countries, state intervention was the only way of creating modern industries from scratch, but also in the advanced capitalist countries the state was needed to rebuild the economy after the war and to improve the general environment where private capitalists could flourish. Whether they were democracies or dictatorships, underdeveloped or developed, bourgeois regimes everywhere relied on massive public intervention to achieve growth.

These interventions were not simply monetary or fiscal; they implied a strong, direct, long term role of the state as owner and developer of entire economic sectors to the point that we even had five-year plans in imperialist countries like France. The boom was so strong that every critic of Keynes, both among the bourgeois and on the left, was marginalised. There were even so-called “Marxists” who wrote books praising Keynesian economic policies as being responsible for the boom. However, although those same critics of Keynesian policies were not aware of it because of the success that such methods seemed to be having in regulating the cycle, the so-called Keynesian “automatic stabilisers” were introducing enormous rigidities in the functioning of the capitalist economy. Bretton Woods, full employment, the welfare state, were all things capitalism could tolerate because of the most powerful economic upswing in its history:

“While keeping the advanced capitalist economies relatively stable, however, Keynesian demand management also left them increasingly stagnant, for, as time went on, governments could secure progressively less additional growth of GDP for any given increase in deficit spending—in the parlance of the era, less bang for the buck. The growth of public borrowing, as well as the additional private borrowing it made possible, did sustain purchasing power, and in that way prevented profitability from falling even further than it otherwise would have, keeping the economy turning over. The resulting additions of purchasing power were especially critical in reversing the severe cyclical downturns of 1974-5, 1979-1982, and the early 1990s, which were far more serious than any during the first postwar quarter century and would likely have led to profound economic dislocations in the absence of the large increases in government and private indebtedness that took place in their wake. Nevertheless, the ever increasing borrowing that sustained aggregate demand also led to an ever greater build-up of debt, which, over time, left firms and households less responsive to new rounds of stimulus and rendered the economy ever more vulnerable to shocks.”[25]

Its failure as a means of avoiding crises meant also that at the theoretical level Keynesianism was now being marginalised. The high point of the scientific rejection of Keynes came in the 1980s, when mainstream economics reverted to the “free market” mantra. Now the best economic policy was no policy at all, with unemployment seen as something brought onto the workers by the workers themselves, and its cure was the elimination of trade unions and so on. We have already explained why this attempt to go back to the good old days of free market capitalism was doomed from the very beginning.

Now, after decades of theoretical justification of globalisation, we are back to Keynesianism, although in a new form. So we have had scores of articles about a return to Keynes, even to Marx [26]. The old orthodoxy has been exposed as useless and the crisis has been, “an intellectual as much as an economic crash”[27]. Once again, bourgeois economists are forced to return to reality from the cyclical mantra that, as a famous book put it, “this time is different”. Recently, Borio, Director of Research at the Bank for International Settlement, pointed out the problem:

“So-called ‘lessons’ are learnt, forgotten, re-learnt and forgotten again. Concepts rise to prominence and fall into oblivion before possibly resurrecting. They do so because the economic environment changes, sometimes slowly but profoundly, at other times suddenly and violently. But they do so also because the discipline is not immune to fashions and fads.”[28]

This is true, but the question is why these fashions and fads recur. The answer is that they are rooted in the profit needs of the capitalists. In the 1960s state-run industries were good for profits. But this was no longer the case in the 1980s, and yet the state is now more decisive than ever to bolster profits and anti-Keynesian theories are once again considered irrelevant as the bourgeoisie is more and more annoyed with its own theoreticians.

However, what the latter have to help them understand the situation is historical experience. This might seem obvious to anyone, but it is not so. To bourgeois economists history is anathema, a useless series of facts no one is interested in. This is because, for the ruling class, the very existence of historical experience is an unpleasant fact, as it shows that different societies are born, live and die, and therefore, capitalism too will not go on for ever. Now, however, desperate for an understanding of the present events, even history is back in fashion[29]. Of course, it is not sufficient to accept that history is part of the necessary tools to study society, to actually understand capitalism. Quite the contrary. In general, the present state of the social sciences is one of deep crisis, just like capitalism, with no viable alternative in sight.

Keynesian economists would seem to be better positioned. Like zombies in a horror movie, the crisis has pushed them out of the grave. Undoubtedly, they are closer to the real world than the average bourgeois economist who considers more competition as the solution to any social disease. And yet, what are their proposing? If we look at the proposals of the more well known among them such as Stiglitz or Krugman, have they come up with any valid measures? They are against austerity, which is a good starting point, but their solution – economic growth based on government spending and debt – is precisely what is causing the crisis to be so deep and long-lasting. And the problem of present-day debt is not a small one. It cannot be solved by inflation without wiping away the banking system. The political consequences of such a choice would be enormous. What about competitive devaluations, with countries devaluing their currency in order to boost exports? This is the magic solution to stagnation, according to standard Keynesianism. Needless to say, it could work if only a couple of minor countries were to take that road in an attempt to export their way out of the crisis. When every nation debases its currency, the tool is ineffective and produces trade wars and political resentment.

In the concrete conditions that capitalism finds itself in today – with the biggest crisis in the history of capitalism; a truly global crisis on an unprecedented scale – Keynesian policies, and reformist policies in general, are completely utopian.

The example of modern day China, which has undertaken Keynesian policies on an enormous scale – creating a housing bubble, unsustainable levels of debt, and increased problems of excess capacity in key sectors – only serves to show the impossibility of Keynesian policies in the concrete situation at the current time, Similarly, the implementation of austerity rather than Keynesian policies by social democratic governments in Greece, Spain, Portugal, and now France also, shows that there is no room for reformism and Keynesian any more. There is no alternative under capitalism but austerity. The question is not over this or that tax; this or that regulation; this or that reform – the real question is: which class decides economic policy, in other words, what is the social nature of the state?

This has always been a weakness of Keynesianism. Contrary to the Social Democratic prejudice, a bigger intervention of the state in the economy is not in itself a “left” policy. Already in the 1970s, the Marxist economist O’Connor explained, using comparative studies of advanced countries, that there was no correlation between the strength of the left and a bigger role for the state[30]. “More Keynes” does not mean, automatically, higher wages, a fairer society, more welfare state and so on. Only class struggle – and ultimately the socialist transformation of society – can bring about these goals.

Keynesian polices are unfeasible because they are rooted in an epoch of capitalism that has long passed. As long as the big banks and capitalist monopolies rule over the state, full employment, an efficient welfare state and so on are only dreams.

The reformists call for a strong public presence in the banking sector; for public investment to reduce unemployment and so on. Of course we are all in favour of reducing unemployment, increasing, spending on public services, and raising wages: how can one disagree with such reforms and measures? The problem is these measures cannot return the world to the 1960s, any more than listening to the Beatles can. Keynesianism today is ruled out. What is needed is to fundamentally change the laws under which the economy operates: to abolish the anarchy and chaos of capitalism; to take over the banks and big businesses and put them under a rational plan of production; in short, to carry out the socialist transformation of society. This is the only alternative.

[1] J. M. Keynes, 1923, A Tract on Monetary Reform, Chapter 3.

[3] See P. Baran and P. Sweezy, 1965, Economics of Two Worlds.

[5] Cecchetti et al., 2010, The future of public debt: prospects and implications, http://www.bis.org/publ/work300.pdf.

[6] Cecchetti et al. cit.

[7] R. Brenner, 2009, What is Good for Goldman Sachs is Good for America The Origins of the Present Crisis, http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/issr/cstch/papers/BrennerCrisisTodayOctober2009.pdf.

[9] “BOE discussed Negative Interest Rates”, WSJE 27.2.2013.

[10] “The negative option”, The Economist, 1.6.2013.

[11] Moseley F., Is the U.S. Economy headed for a Hard Landing? , https://www.mtholyoke.edu/courses/fmoseley/HARDLANDING.doc.

[12] Moseley, cit.

[13] http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-04-24/gold-rout-for-central-banks-buying-most-since-1964-commodities.html.

[16] Keynes, cit., Chapter IV.

[17] See for instance, the case of Korea and Taiwan: http://www.marxist.com/how-capitalism-developed-in-taiwan-pt-one.htm.

[19] E. Stockhammer, 2010, Financialisation and the Global Economy, http://www.peri.umass.edu/236/hash/c054892e7a23115bfbd0c22c9e90f57c/publication/432/.

[20] Graph from Taylor, The Great Leveraging, 2012.

[21] J. Crotty, 2008, Structural Causes of the Global Financial Crisis: A Critical Assessment of the ‘New Financial Architecture’, http://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=econ_workingpaper.

[22] Graph from Stockhammer, cit.

[23] A. Greenspan, 2007, The Age of Turbolence, p. 231.

[24] T. Palley, 2007, Financialisation: What It Is and Why It Matters, http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_525.pdf.

[25] Brenner, cit.

[26] For instance, see the recent article of the Time about “Marx’s revenge” (http://www.marxist.com/the-resilience-of-the-ideas-of-karl-marx.htm, and http://business.time.com/2013/03/25/marxs-revenge-how-class-struggle-is-shaping-the-world/).

[27] A. M. Taylor, 2012, The Great Leveraging, http://www.nber.org/papers/w18290.

[28] C. Borio, 2012, The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt?, http://www.bis.org/publ/work395.htm.

[29] For instance, Jorda et al., 2010, Financial Crises, Credit Booms, and External Imbalances: 140 Years of Lessons (http://www.ecb.europa.eu/events/conferences/shared/pdf/net_mar/Session1_Paper2_Jorda_Schularick_Taylor.pdf?5fc02e3a1cf2f994aff3170a89fdab74).

[30] J. O’Connor, 1979, The fiscal crisis of the State, Chapter VII.